Cutting prototyping to save time or expense is one of the most reliable ways to lengthen a medical device development program. When prototyping is undervalued and treated as an optional expense rather than a requirement, cost and schedule risk almost always increase downstream. In practice, it defers learning until changes are slow, expensive, and difficult to absorb. When applied deliberately and by using a clear prototype strategy, prototyping reduces overall development cost and compresses timelines by exposing technical, usability, and integration risks early, when they are fastest and least expensive to address.

This article frames prototyping as a learning and decision making activity, not as a reduced version of full product development. From a regulatory perspective, only two considerations apply during prototyping: capturing documentation at a level appropriate for eventual inclusion in the Design History File (DHF), and recognizing that any clinical use testing carries substantially higher requirements. Because those requirements closely resemble full product development rigor, clinical testing is not addressed here.

The Purpose of Prototyping in Medical Device Development

The primary purpose of prototyping is to learn quickly. Rapid learning enables faster innovation by allowing teams to explore ideas, test assumptions, and make informed decisions early, while the cost of change remains low. Prototyping shortens feedback loops by turning questions into evidence and assumptions into data.

A key outcome of accelerated learning is the reduction of uncertainty across technical, usability, integration, and manufacturability domains. Uncertainty that persists late into development drives redesign, rework, and verification delays, often at an order of magnitude higher cost than early changes. Prototyping shifts this learning forward in time, when adjustments are still straightforward and inexpensive.

Well executed prototyping also supports parallel progress across engineering disciplines. By exposing high risk assumptions early, prototyping reduces downstream friction during integration, verification, and validation, resulting in development programs that move faster and with fewer late stage surprises.

Levels of Prototype Fidelity

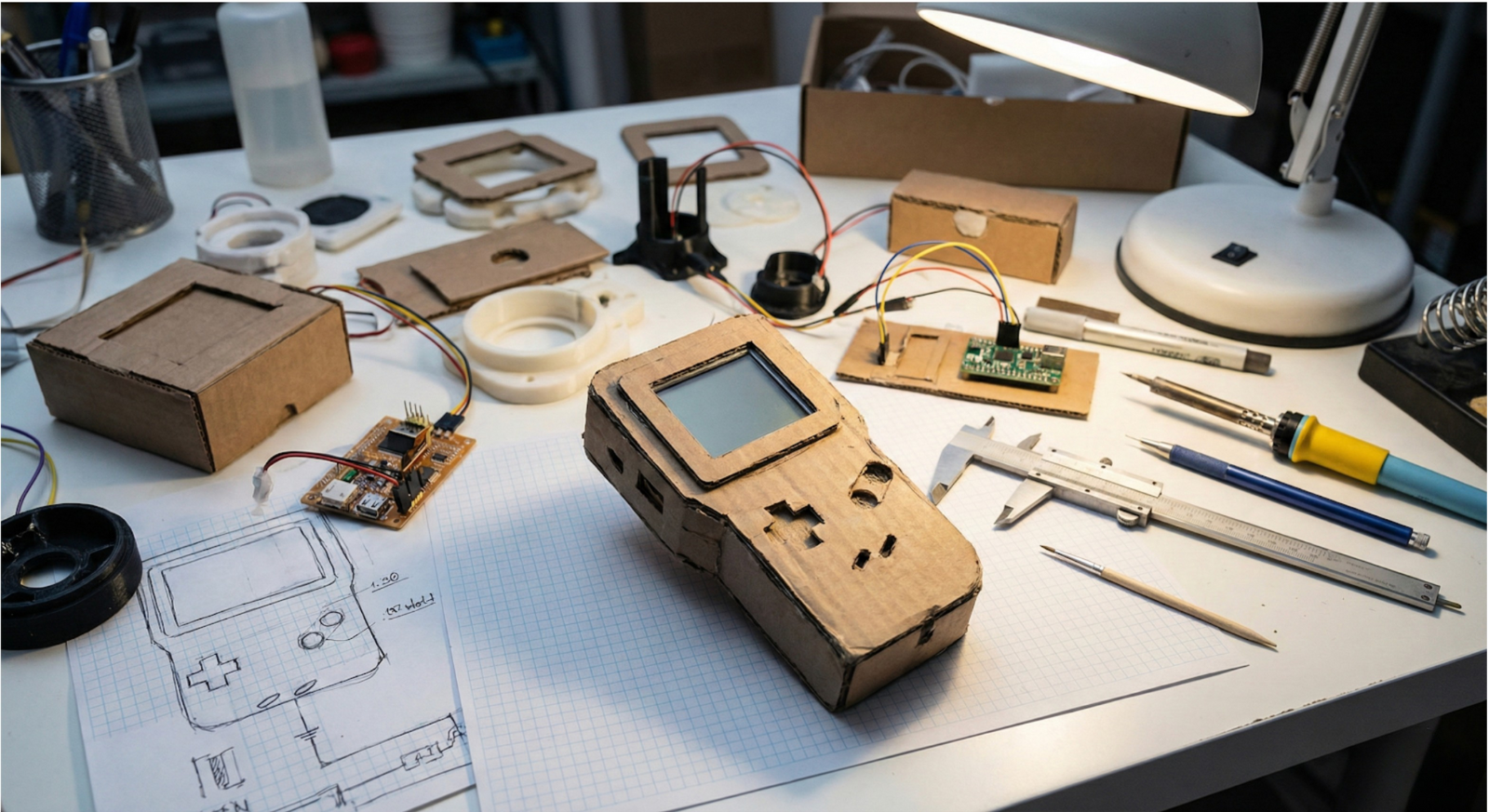

Prototype fidelity should be guided by the cost of being wrong. Early proof of concept prototypes are often simple, incomplete, and intentionally rough. Their role is to establish feasibility or invalidate ideas quickly. Functional prototypes increase fidelity only where necessary, allowing teams to explore performance, interaction, or integration risks. High fidelity or production intent prototypes are justified only when realism is required to answer a specific question.

In practice, multiple low fidelity prototypes often deliver more value than a single polished build. Increasing fidelity too early slows iteration, obscures root causes, and creates unnecessary attachment to designs that should remain disposable.

Engineering Disciplines Considered in Prototyping

Depending on the device and its risk profile, prototyping may involve multiple engineering disciplines. These commonly include mechanical engineering, electrical and electronics engineering, software engineering, fluidic or pneumatic engineering, manufacturing and industrial engineering, test and verification engineering, chemical engineering such as coatings, reagents, or material interactions, and packaging engineering, where protection, sterility maintenance, and usability are often evaluated early.

Each discipline may be prototyped independently or in combination, depending on which uncertainties are most critical to resolve at a given point in development.

Intelligent Prototype Strategy: Combining Disciplines and Making Tradeoffs

An effective prototype strategy prioritizes learning efficiency over completeness. Combining multiple engineering disciplines into a single prototype is appropriate when the interaction between those disciplines represents the primary risk. Examples include mechanical and electrical integration to simulate system behavior, or partial hardware combined with software to evaluate control strategies or user interaction.

Combining disciplines too early, however, can introduce unnecessary complexity and make failures difficult to diagnose. When risks are largely isolated, separating disciplines enables faster iteration. User interfaces can often be evaluated using physical or visual mockups disconnected from live code. Software can be tested against simulated sensors or actuators. Mechanical mechanisms can be exercised without electronics installed. These approaches preserve learning speed while keeping prototypes focused.

Tradeoffs in prototype production are not only acceptable, but they are often essential. Prototype materials may be less durable, non sterilizable, or incompatible with planned manufacturing processes such as welding, molding, or surface decoration. These compromises are appropriate as long as they do not interfere with the question being answered. Manufacturing methods may be simplified to reduce lead time, assemblies may be manual rather than automated, and cosmetic finish may be deprioritized unless aesthetics are under evaluation.

Effective prototyping requires deliberate choices about what must be real, what can be simplified, and what can be simulated.

Common Prototyping Pitfalls

Several recurring mistakes reduce the effectiveness of prototyping. One of the most common is over polishing prototypes too early. Prototypes that appear complete or production ready can create a false sense of progress and invite unrealistic timeline expectations from stakeholders who may not yet appreciate how much technical development, integration work, and risk remain. This often leads to premature schedule commitments and pressure to lock designs before learning is complete.

Other pitfalls include combining engineering disciplines before individual risks are understood, which introduces confusion rather than clarity, and ignoring non mechanical subsystems, which delays discovery of critical integration issues. Waiting too long to build anything tangible frequently results in avoidable late stage surprises.

Prototyping as a Cost and Time Reduction Strategy

When approached strategically, prototyping is not an added expense or schedule burden. It is a risk reduction engine and a schedule compression tool. By enabling faster learning, clearer decisions, and earlier integration insight, effective prototyping prevents far larger costs and delays later in development. The goal is therefore not to minimize prototyping, but to maximize the effectiveness of the prototype program so that it accelerates learning, reduces late stage risk, and enables better decisions long before they become expensive to change.

Strategic Prototype Review

If you have an active development plan, we offer a free 30-minute review to identify where strategic prototypes can reduce risk, accelerate decisions, and improve downstream outcomes.

Email: sdonnigan@a65consulting.com

Or schedule your design process review online

References

- ISO 13485:2016 – Medical devices: Quality management systems

https://www.iso.org/standard/59752.html - Design Controls for Medical Devices

U.S. Food & Drug Administration

https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/design-controls-medical-devices - Product Design and Development

Karl T. Ulrich, Steven D. Eppinger

https://www.mheducation.com/highered/product/product-design-development-ulrich/M9781260043655.html - Experimentation Matters: Unlocking the Potential of New Technologies for Innovation

Stefan Thomke

https://www.hbs.edu/faculty/Pages/item.aspx?num=40348

Revolutionizing Product Development

Kim B. Clark, Steven C. Wheelwright

https://www.simonandschuster.com/books/Revolutionizing-Product-Development/Kim-B-Clark/9780684839912